"When time is broken and no proportion

kept!....I wasted time, and now time doth waste

me."-Shakespeare, Richard II, Act 5, Scene 5

Aristotle's ‘good life’ is guided by virtue. The virtues have been discussed in

these blog posts, but how many of us guide our lives by them? When was the last

time you reflected on them, or sat down over a beer or a glass of wine and

discussed them with friends? Or asked yourself, ‘how am I doing?’ We rarely discuss

living a ‘good life’ because we never take the time to define what that means

for our individual lives. In the modern world few are interested in such

things, not even you dear reader.

In truth, our

society does not value reflecting on what it means to live a good life. Rather we are taught and told what it

is. Go to school, get good grades, then a job, etc., etc. In between have some

fun. Near the end maybe you’ll have a little money so you can sit around

accomplishing nothing while waiting to die. So if you do not define your ‘good life,’

it will be done for you.

Socrates said “the

unexamined life is not worth living.”[i] Socrates offered these words as his defense for

charges of ’impiety and corrupting the youth’ while practicing philosophy on

the streets of ancient Athens over 2400 years ago. He was found guilty and sentenced

to death for questioning how Athenians were living their lives. (Such inquiries

have rarely been encouraged, even today.) Unlike Socrates, our physical lives are not at risk for philosophical self-examination, for holding ourselves accountable to

living a ‘good life,’ but we rarely do so. And yet we readily accept being accountable to others.

Lawyers, as well as other professionals, are accountable to their employers and clients for their time in order to be compensated. Indeed most professionals will ‘log’ about 80,000 hours on average (totaling 9 years) during their working lives.[ii] These time ‘logs’ are useful for getting compensated but nothing more. If someone picked up all 9 years’ worth and read them they would learn virtually nothing about who the person was, what they thought, or whether they had lived a ‘good life.’ Logging 9 years’ worth of time offers little towards determining whether or not you are leading a ‘good life.’ To do that requires reflection.

The Stoic philosopher

Seneca wrote “I will keep constant watch over myself…and will put each day up

for review.”[iii]

Seneca defined his ‘good life’ by living according to Stoic philosophy. At the end of each day he would take a few

minutes to hold his life up to account, to reflect on whether he was being true

to himself, living the life he chose. When

this activity is suggested the usual refrain is ‘I'm too busy’ or ‘I don’t have time.’ Of course

this is often said by those who will spend 2 days, 22 hours and 18 minutes

watching Game of Thrones, or checking

social media throughout their ‘busy’ day.[iv]

Have you wasted time? Imagine

looking over your past through time’s distant mirror and seeing all the wasted

time piled up. Those ‘piles’ represent your then future self. The self that

wasn’t. You owed that wasted time to your future self to develop a philosophy

of life, then to hold yourself to account, and to put your life up for regular

review. Don’t let another day, week or month get added to the mounds of time

you have already wasted by not setting goals and standards for directing your

life. Aristotle said “you cannot judge a [persons] life until it is completed.”[v] So

if you are reading this it is not too late to define your ‘good life,’ and to begin

living it.

[i]

Plato, The Apology

[ii]

80,000hours.org

[iii]

Seneca, Moral Letters, 83.2

[iv] https://www.komando.com/downloads/binge-watchers-find-out-how-long-your-show-will-take-to-finish/469781/;

on average the daily time spent on social media is 144 minutes a day; The Roman Emperor Marcus

Aurelius ruled over the greatest empire of the ancient world and yet found time

to reflect on his daily activities, to hold himself to account. These personal journals

were kept for the purpose of self-improvement and for reflection on living his

life according to Stoic philosophy.[iv]

He was loyal to this daily habit even

while on military campaigns.

https://www.broadbandsearch.net/blog/average-daily-time-on-social-media.

[v]

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, 1097b-1098ai9. Aristotle understood that our decisions,

how we live our lives, has ramifications beyond out mortal lives, and thus a

life might not be ‘complete’ until well after death. Or as Russell Crow said in

the movie Gladiator, “what we do in

life, echoes in eternity.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CDpTc32sV1Y

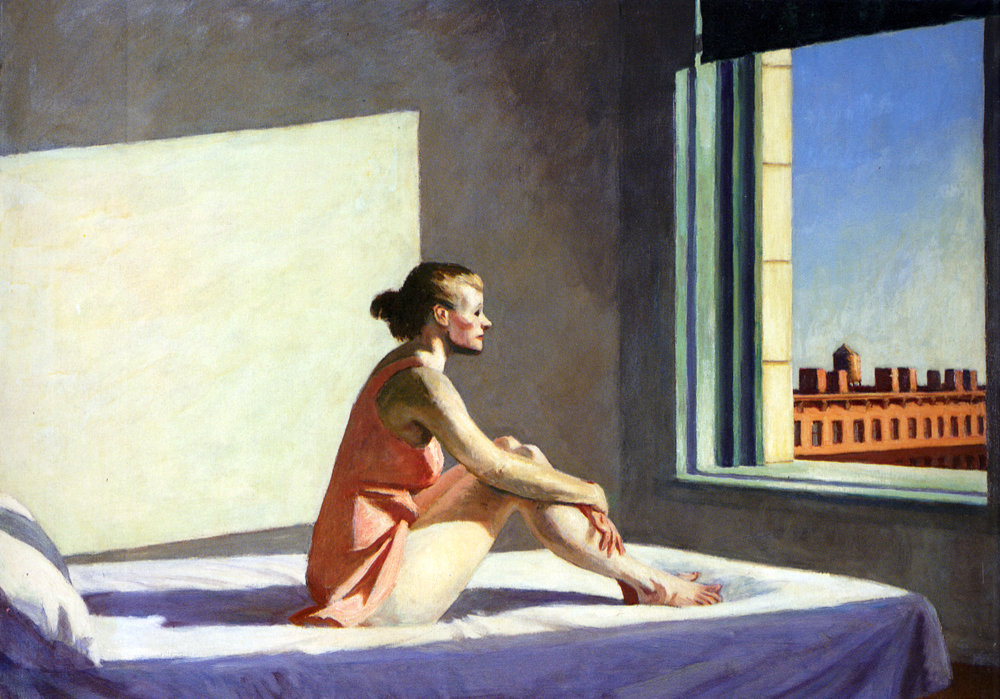

Painting, Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, Rembrandt